It is often asked why good people do bad things. Perhaps the question should be when.

It is often asked why good people do bad things. Perhaps the question should be when.

More likely, it’s in the afternoon or evening. Much less so in the morning.

That’s the finding of research, published in the journal Psychological Science, which concludes that a person’s ability to self-regulate declines as the day wears on, increasing the likelihood of cheating, lying or committing fraud.

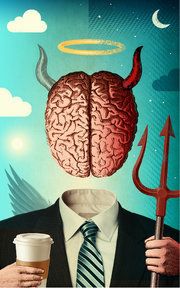

This so-called morning morality effect results from “cognitive tiredness,” said Isaac H. Smith, an assistant professor at the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University and co-author of the article with Maryam Kouchaki, an assistant professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern. “To the extent that you’re cognitively tired,” Dr. Smith added, “you’re more likely to give in to the devil on your shoulder.”

The findings draw from four experiments that convened two groups of subjects, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. In the first experiment, undergraduates looked at different images of dots on a computer screen and reported whether the dots in each image were concentrated on the left side or the right side.

If subjects said the dots were bunched on the right, they earned 5 cents, with a chance to earn up to $5. They could earn the money even if they “cheated” by saying that the dots were concentrated on the right when they were not.

In the first experiment, subjects cheated 25 percent more often in the afternoon. That finding was reinforced in subsequent experiments. The results conform to other research showing the effects of taxing a part of the brain responsible for “executive control.” When that region is worn down — say, by a task as simple as memorizing numbers — it can impinge decision-making, and, by extension, moral judgment.

In a related study, published in 2011, scholars at Harvard and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania showed that participants who performed a task that involved resisting temptation were much more likely to “impulsively cheat” in a subsequent task. Having already used up cognitive energy to resist, the theory went, they were more susceptible to giving in.

The latest findings are not without detractors. In July, another group of scholars offered a commentary arguing that the morning morality effect was an oversimplification. They said the research failed to recognize that some people are night owls and might resist temptation better as the day goes on. Their point was that some brains start out tired, then ramp up during the day.

Dr. Smith and Dr. Kouchaki countered, in essence, that no matter when you felt most alert, brain depletion happened bit by bit over the course of the day.

In fact, Dr. Smith says, brain depletion can come from everyday tasks like choosing what to wear or eat — and the number of these decisions may be mounting as technology creates new choices to be made around the clock. (Do I “like” this Facebook status? Do I write one of my own?) Add these to the economy’s global nature (events happening any time of day), and it suggests to Dr. Smith a simple solution: “Don’t waste time on menial decisions that don’t matter.”